Retina treatment includes a range of medical and surgical procedures used to manage conditions affecting the retina. The retina is a thin layer of light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye that plays a vital role in vision. It converts incoming light into neural signals that the brain interprets as images.

Definition of retina treatment in ophthalmology

In ophthalmology, retina treatment refers to therapies used to repair, stabilize, or preserve retinal structure and function when disease or injury causes damage. These treatments are tailored to the specific condition and may include several different approaches.

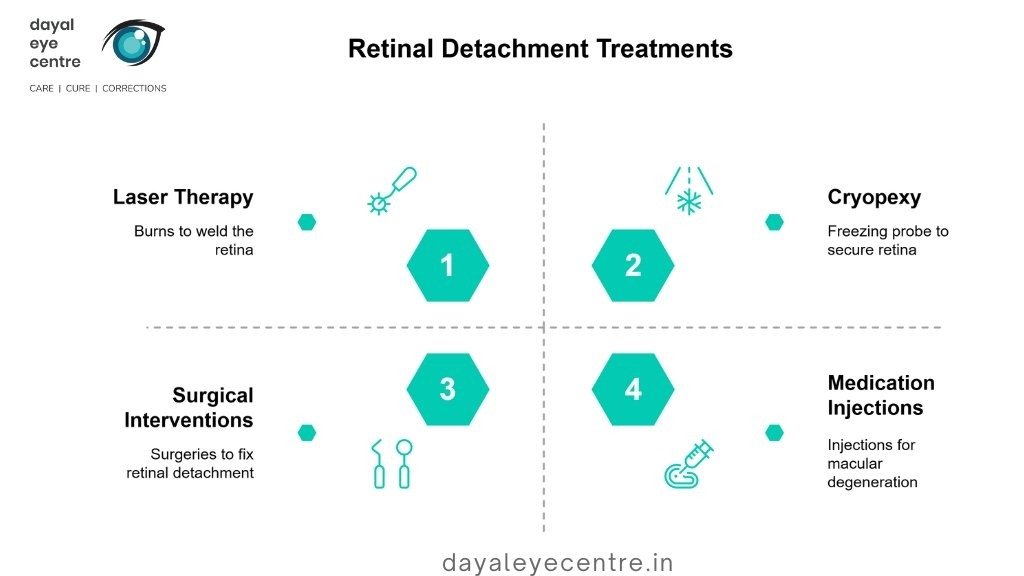

- Laser therapy (photocoagulation): Creates controlled burns around retinal tears, forming scars that “weld” the retina to the underlying tissue.

Cryopexy (freezing treatment): Uses a freezing probe to create scarring that secures the retina to the eye wall.

Surgical interventions: Include pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckle, and vitrectomy.

Medication injections: Primarily used for conditions such as macular degeneration.

Your doctor will choose the most appropriate treatment based on your specific condition, its severity, and its location within the eye. Although these treatments may sound intimidating, they are highly effective, with success rates of about 90% when performed promptly.

Conditions that commonly require intervention

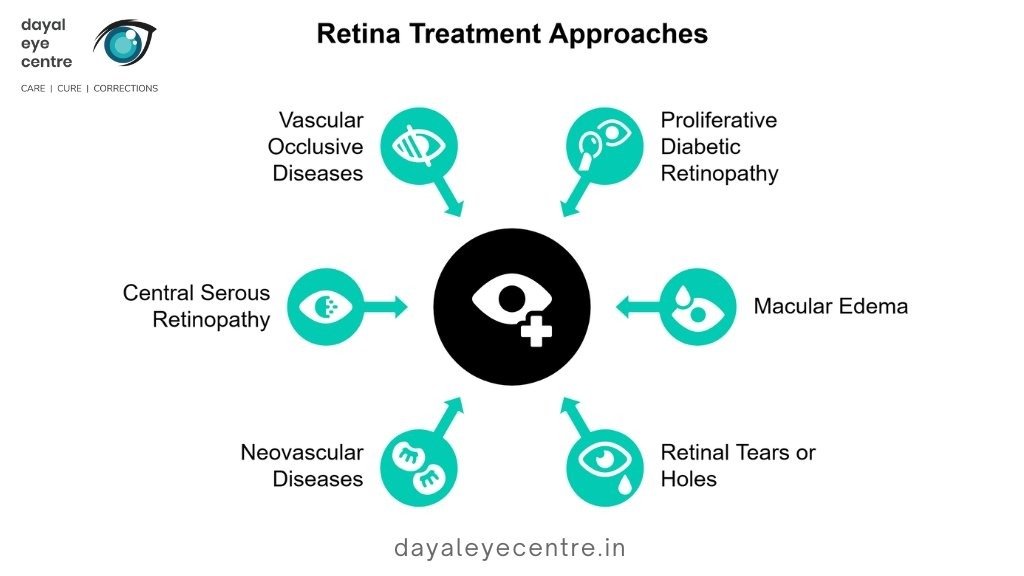

Retinal detachment requires the most urgent care among retinal conditions. Retina specialists also treat:

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: Often managed effectively with laser treatment

- Macular edema: Commonly treated with focal or grid laser therapy

- Retinal tears or holes: Require prompt treatment to prevent detachment

- Neovascular diseases: Including those associated with age-related macular degeneration

- Central serous retinopathy: Treated with photodynamic therapy or Micropulse laser

- Vascular occlusive diseases: Often require a combination of treatment approaches

Timely treatment is critical for most of these conditions. Some, such as diabetic retinopathy, require ongoing management to maintain long-term control.

Retinal detachment pathophysiology overview

Retinal detachment happens when the neurosensory retina pulls away from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid. This separation occurs in three different ways, matching the three types of detachment:

Rhegmatogenous detachment – This is the most common type. It happens when a tear in the retina lets liquefied vitreous fluid leak underneath, which pulls the retina away from supporting tissue. Three things usually happen first:

- The vitreous turns liquid (vitreous syneresis)

- Forces pull and create a retinal break

- Fluid flows through the break into the subretinal space

Tractional detachment – This type occurs when fibrous membranes or scar tissue pull the retina away from the RPE without any retinal tears. It is most commonly seen in advanced diabetic retinopathy, where contracting scar tissue exerts traction on the retina.

Exudative detachment – This form develops when fluid accumulates between the neurosensory retina and the RPE without retinal breaks or traction. The fluid originates from leaking blood vessels, usually due to inflammation, uncontrolled hypertension, or tumors.

Once detachment begins, the separated retina loses its nutritional and oxygen support from the underlying tissues. This leads to photoreceptor damage and cell death. Prompt recognition and treatment are essential, as any delay significantly increases the risk of permanent vision loss. Although retinal detachment is usually painless, it is considered a medical emergency.

Sudden increases in floaters, flashes of light, or shadows in the visual field may indicate retinal detachment and require immediate medical evaluation.

Types of Retinal Detachment and Their Implications

Understanding the different types of retinal detachment helps guide treatment decisions. Each type differs in its mechanism, causes, and management approach.

Rhegmatogenous detachment: tear-induced

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is the most common form and occurs when the retina develops a tear, hole, or break. This allows liquefied vitreous to seep beneath the retina, separating the neurosensory retina from the RPE.

Three conditions are typically required: vitreous liquefaction, tractional forces that create a retinal break, and fluid movement into the subretinal space. With aging, the vitreous gel naturally shrinks and becomes less cohesive, sometimes pulling on the retina strongly enough to cause tears.

This type of detachment may develop rapidly or progress over weeks to months. Risk factors include:

- Increasing age

- Previous eye surgery

- High myopia

- Ocular trauma

- Retinal detachment in the fellow eye

- Inherited disorders such as Stickler syndrome

- Lattice degeneration and other peripheral retinal abnormalities

Tractional detachment: diabetic retinopathy link

Tractional retinal detachment (TRD) occurs without retinal tears or breaks. Instead, fibrous or fibrovascular membranes contract and pull the retina away from its underlying layers.

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause. Approximately 5% of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy develop tractional detachment, even after panretinal photocoagulation. The underlying process includes:

- Chronic hyperglycemia leading to capillary closure and retinal ischemia

- Increased production of growth factors, particularly VEGF

- Formation of abnormal new blood vessels that breach the internal limiting membrane

- Development and contraction of fibrovascular membranes that exert traction

Other causes of tractional detachment include sickle cell retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, ocular trauma, penetrating injuries, and chronic inflammatory eye diseases.

Exudative detachment: fluid accumulation causes

Exudative (serous) retinal detachment occurs when fluid accumulates beneath the retina without retinal breaks or traction. This results from leakage from abnormal blood vessels or disruption of the blood–retinal barrier.

Common causes include:

- Inflammatory conditions such as Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome and posterior scleritis

- Vascular disorders, including severe hypertension and central retinal vein occlusion

- Intraocular tumors such as choroidal melanoma

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Central serous chorioretinopathy

Rhegmatogenous and tractional detachments usually require surgical intervention, whereas exudative detachments often improve with medical or laser treatment aimed at the underlying cause rather than mechanical repair.

All forms of retinal detachment require urgent medical attention due to the risk of permanent vision loss. Identifying the specific type helps clinicians choose the most appropriate treatment and better predict visual outcomes.

How Retinal Detachment Is Diagnosed

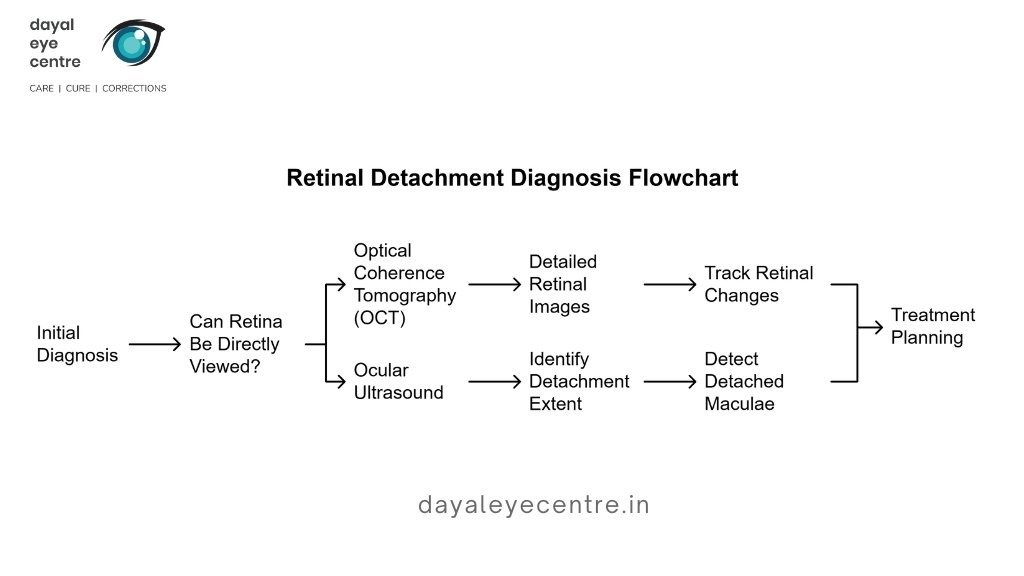

Rapid diagnosis is essential for successful management of retinal detachment. Eye specialists use several complementary techniques to confirm detachment and assess its extent.

Retinal exam with dilation

Diagnosis begins with a comprehensive dilated eye examination. Eye drops are used to widen the pupil, allowing a clear view of the retina. This examination is painless and enables direct visualization of retinal tears, breaks, or detached areas. Gentle pressure on the eyelids (scleral depression) may be required to examine the peripheral retina, which some patients find mildly uncomfortable.

An ophthalmoscope with bright illumination and specialized lenses is used to evaluate the retina. Peripheral fundus examination may be performed using indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, or a three-mirror contact lens to detect detachments that might otherwise be missed.

OCT and ultrasound for structural imaging

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution cross-sectional images of retinal layers. It allows precise assessment of retinal structure at diagnosis, before treatment, and during follow-up to monitor healing and anatomical changes.

Ocular ultrasound is especially useful when the retina cannot be visualized directly due to vitreous hemorrhage, dense cataract, or other media opacities. Studies show that ultrasound can identify the extent of retinal detachment within three clock hours in over 94% of cases and detect macular involvement in approximately 90% of patients prior to surgery. B-scan ultrasonography and standardized echography together provide reliable evaluation when direct visualization is limited.

Fluorescein angiography for blood vessel analysis

Fluorescein angiography involves injecting a yellow dye (fluorescein) into a vein in the arm. The dye travels through the bloodstream within 10–15 seconds and reaches the blood vessels of the eye, causing them to fluoresce. A specialized camera captures images as the dye flows through the retinal circulation. These images reveal abnormalities that may not be visible during a routine eye examination.

This test is most commonly used for conditions such as diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration. It helps differentiate between various retinal disorders by identifying characteristic leakage patterns. For example, it can distinguish diabetic macular edema from pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Fluorescein angiography is particularly useful in patients with high myopia and recent vision loss, as choroidal neovascularization may not always be apparent on clinical examination.

Surgical and Non-Surgical Retina Treatment Options

Treatment options for retinal conditions range from minimally invasive procedures to complex surgical interventions. The choice of treatment depends on the severity and type of retinal pathology.

Laser therapy and cryopexy for minor tears

Small retinal tears or holes without detachment can be treated with laser photocoagulation or cryopexy. Laser therapy creates controlled burns around the tear, forming scars that secure the retina to the underlying tissue. This outpatient procedure is performed through the pupil, and patients may notice flashes of light during treatment.

Cryopexy uses a freezing probe applied externally to the eye directly over the tear. The cold induces scar formation that stabilizes the retina. The eye is numbed beforehand, and patients may feel pressure or a cold sensation. Both treatments typically require patients to rest and avoid strenuous activity for one to two weeks during healing.

Pneumatic retinopexy for localized detachment

Certain localized retinal detachments, particularly those involving the superior eight clock-hours of the fundus, may be treated with pneumatic retinopexy. In this office-based procedure, a gas bubble (SF₆ or C₃F₈) is injected into the vitreous cavity to press the detached retina back against the eye wall. Laser photocoagulation or cryopexy is then used to seal the retinal tear.

Strict head positioning is essential after the procedure, often for up to one week, to keep the gas bubble in the correct position. Success rates range from 71–84% in phakic patients and 41–67% in pseudophakic patients.

Scleral buckle for structural support

A scleral buckle procedure attaches a silicone band or sponge to the eye’s white part (sclera). This creates an indentation that eases vitreous traction on the retina. The surgery pushes the eye wall toward the detached retina to help it reattach. Most buckles stay in place permanently and have impressive success rates of 80-90%.

Vitrectomy for complex or recurrent cases

Vitrectomy is used for complex or recurrent retinal detachments. The surgeon removes the vitreous gel, peels tractional membranes, and replaces the vitreous with air, gas, or silicone oil to flatten the retina. In difficult cases, vitrectomy may be combined with scleral buckling. The procedure typically lasts about two hours, and approximately 90% of detachments are successfully repaired with a single operation.

Medication injections for macular degeneration

Anti-VEGF injections are the primary treatment for wet age-related macular degeneration. Common medications include Lucentis, Eylea, Beovu, Vabysmo, and Avastin. These drugs are injected directly into the eye to inhibit abnormal blood vessel growth and reduce leakage. Treatment stabilizes vision in about 90% of patients and improves vision in approximately one-third. Injections are usually required every 4–12 weeks, depending on the medication and response.

What to Expect After Retina Treatment

Recovery after retinal treatment requires patience and close adherence to your doctor’s instructions. Healing time varies depending on the procedure and individual factors.

Vision improvement timeline

Your vision stays blurry for several weeks after surgery. Most patients see improvements 4-6 weeks after the procedure. Full stabilization takes longer – your vision might take months to return to normal. The retina needs a year or more to heal completely. Each procedure has its own timeline: pneumatic retinopexy takes 3+ weeks, while scleral buckle and vitrectomy need 4+ weeks. Your vision should get better step by step rather than all at once.

Possible complications: cataracts, pressure changes

All retinal procedures carry some risk. Potential complications include infection, internal bleeding, elevated intraocular pressure, glaucoma, and cataract formation. In some cases, additional surgery may be required due to incomplete reattachment or recurrent detachment. Contact your doctor immediately if you experience worsening vision, severe pain, or significant swelling after treatment.

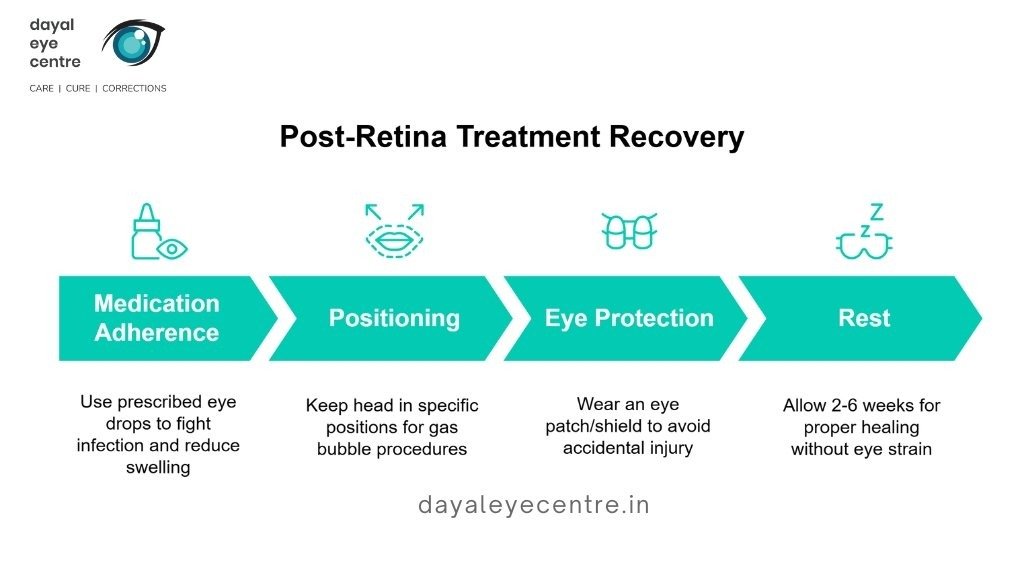

Post-surgery care: eye patch, head position, drops

Proper postoperative care is essential for optimal recovery. Key elements include:

- Medication adherence: Use prescribed eye drops to prevent infection and reduce inflammation

- Positioning: Maintain recommended head positions (often face-down) for up to seven days when a gas bubble is used

- Eye protection: Wear an eye patch or shield initially to prevent accidental injury

- Rest: Allow two to six weeks for recovery, avoiding eye strain and strenuous activities

When to resume normal activities

Normal activities should be resumed gradually. You may return to office-based work after one to two weeks, but physically demanding jobs usually require a longer recovery period. Avoid heavy lifting, bending, and strenuous exercise for at least two weeks. Sexual activity may typically be resumed after one week, but caution is required if a gas bubble is still present in the eye. Driving should be avoided until vision has stabilized and your doctor confirms that it is safe.

Conclusion

Retinal detachment is a serious eye emergency that requires prompt medical attention. This guide has covered the three main types of retinal detachment—rhegmatogenous, tractional, and exudative—each with distinct causes and treatment approaches. Early and thorough eye examinations are essential, especially for individuals with high myopia, prior eye injuries, or conditions such as diabetic retinopathy.

When patients seek care promptly after noticing warning signs—such as sudden flashes of light, an increase in floaters, or shadow-like changes in vision—doctors can successfully treat approximately 90% of cases. Treatment options range from laser therapy and cryopexy for small retinal tears to more complex surgical procedures, such as vitrectomy, for advanced cases. Understanding these options helps patients make informed decisions alongside their ophthalmologists.

Vision recovery typically occurs gradually over several weeks following retinal treatment. Long-term outcomes depend greatly on adherence to post-operative instructions, including maintaining proper head positioning, using prescribed eye drops, and avoiding strenuous activities. Although some patients may develop complications such as cataracts or changes in eye pressure, most achieve successful retinal reattachment with appropriate care.

Modern retinal treatments are highly effective, but regular eye examinations remain the best defense against vision loss. While the healing process takes time, preserving vision is well worth the effort. Acting quickly when unusual visual symptoms arise can make a critical difference in saving sight.

FAQs

When is retina surgery necessary?

Retina surgery is required when the retina detaches from its normal position. This is a medical emergency that demands immediate treatment to prevent permanent vision loss. Surgery is usually necessary for retinal tears, holes, or detachments that cannot be managed with less invasive treatments such as laser therapy or cryopexy.

What are the common symptoms of retinal problems?

Common symptoms include sudden flashes of light, a rapid increase in floaters, blurred or distorted vision, difficulty seeing in low light, and the appearance of a dark shadow or curtain across the field of vision. Any of these symptoms warrant immediate medical evaluation.

How successful are retina treatments?

Retina treatments—particularly for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment—have a high success rate of approximately 90% when performed promptly. Outcomes vary depending on the type and severity of the condition and how quickly treatment is initiated.

What does recovery after retina treatment look like?

Recovery is gradual. Vision is often blurry for several weeks, with noticeable improvement typically occurring within four to six weeks. Complete visual stabilization may take several months, and full retinal healing can take a year or longer. Careful adherence to post-operative instructions is essential for optimal recovery.

Can retinal detachment be treated without surgery?

In rare cases, retinal detachment caused by fluid accumulation without retinal tears may resolve with medical treatment of the underlying condition. However, most retinal detachments—especially those involving tears or holes—require surgical intervention to preserve vision.