Your retina is a direct extension of your central nervous system. Doctors place great value on the retina because it is the only part of the brain that can be examined directly without surgery or invasive testing. Located at the back of the eyeball, this thin tissue layer—only about 0.5 mm thick—forms the innermost layer of the eye, positioned between the vascular choroid and the tough fibrous sclera.

The retina functions as a biological converter. When light enters the eye, this specialized tissue captures light particles (photons) and converts them into electrical and chemical signals. These signals travel through nerve pathways to the brain, where they are interpreted as the visual world you experience.

The retina contains approximately 6 million cone cells and more than 100 million rod cells, each serving a distinct role in vision:

- Rod cells: Function best in low-light conditions and are primarily located in the peripheral retina, supporting night and peripheral vision.

- Cone cells: Operate optimally in bright light and are responsible for color vision. Three types of cones detect blue, green, and red wavelengths.

Structurally, the retina is composed of ten distinct layers, each playing a critical role in visual processing. Of particular importance is the macula, a yellowish region responsible for sharp, detailed vision. At the center of the macula lies the fovea, where cone cells are densely packed, enabling precise central vision required for reading, facial recognition, and fine visual tasks.

The retina has exceptionally high metabolic demands and consumes more oxygen than any other tissue in the body. To meet this demand, the eye relies on a unique dual blood supply system that supports the inner and outer retinal layers separately, ensuring efficient oxygen and nutrient delivery.

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), the outermost retinal layer, plays a key role in maintaining the blood–retinal barrier along with the retinal blood vessel lining. The RPE performs multiple essential functions, including fluid and ion transport, photoreceptor support, and the production of growth factors and signaling molecules.

Damage to the retina can have serious and lasting consequences. Many retinal diseases significantly impair vision and quality of life. Understanding retinal function explains why conditions such as macular degeneration or retinal detachment require urgent medical attention—once damaged, the retina may be unable to transmit visual information effectively to the brain, potentially leading to permanent vision loss.

Retinal development begins in the fourth week of pregnancy and continues through the first year of life. This prolonged developmental period makes the retina particularly vulnerable to genetic and environmental influences that can disrupt normal formation.

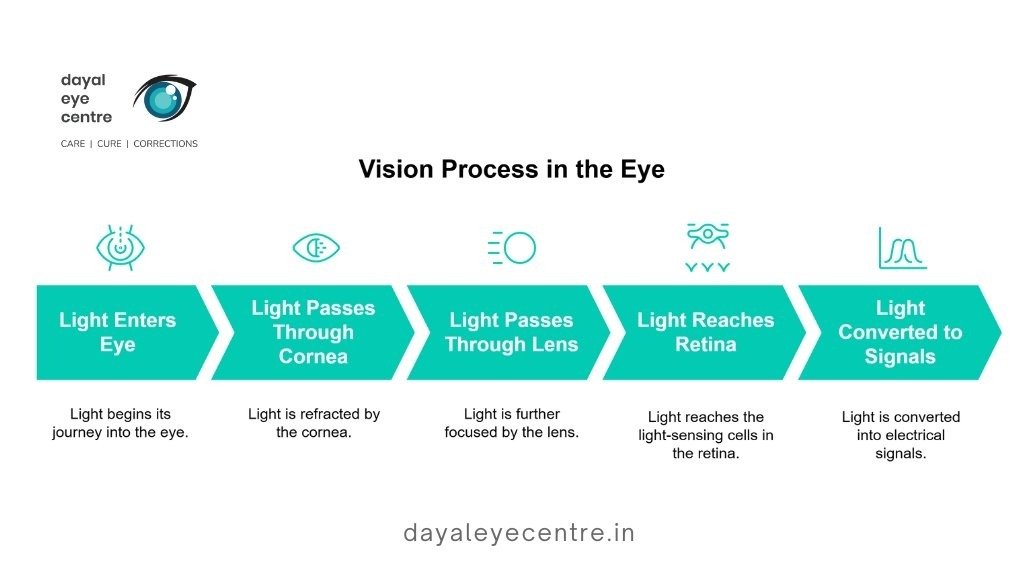

How the Retina Processes Light into Vision

Vision begins through a highly complex and precise process within the eye. As light enters, it passes through the cornea and lens before reaching the light-sensitive cells within the retinal layers. This marks the first step in transforming light into the visual perception that allows you to see the world around you.

Photoreceptor Role in Light Detection

Photoreceptors act as the light-detecting cells within the retinal structure. These specialized cells contain light-sensitive proteins that capture light particles and initiate the visual process. The retina has two primary types of photoreceptors:

- Rod cells: Highly sensitive to light, rods enable vision in dim conditions and dominate peripheral vision. They outnumber cones by approximately 20:1 across most of the retina.

- Cone cells: Concentrated mainly in the central retina, cones function best in bright light and are responsible for color vision and fine detail.

Unlike most neurons that activate when stimulated, photoreceptors are active in darkness and reduce their activity when exposed to light. This unique response occurs through a complex biochemical cascade known as phototransduction.

During phototransduction, light alters the structure of light-sensitive proteins within photoreceptors. In rods, light striking rhodopsin triggers a conformational change that initiates a series of molecular events, ultimately signaling the presence of light.

Signal Transmission to the Brain via Optic Nerve

After photoreceptors detect light, the retina processes this information before transmitting it to the brain. Signals first pass from photoreceptors to bipolar cells, with horizontal and amacrine cells modifying and refining these signals.

The processed information then reaches retinal ganglion cells—the only retinal neurons that generate action potentials. The axons of these cells converge at the optic disc to form the optic nerve, which carries visual information to the brain. Although the retina contains over 130 million photoreceptors, the optic nerve comprises only about 1.2 million fibers, highlighting the retina’s role in compressing visual data.

At the optic chiasm, fibers from the nasal (inner) halves of each retina cross to the opposite side, while temporal (outer) fibers remain uncrossed. Visual signals then travel through specific brain pathways to the visual cortex, where conscious visual perception occurs.

Function of Retina in Human Eye: Color, Detail, and Motion

The retina performs several advanced visual functions:

- Color vision: Three types of cone cells are sensitive to red, green, and blue wavelengths. When viewing a yellow object, both red- and green-sensitive cones are activated, and the brain interprets this combined signal as yellow.

- Detail vision: Fine visual detail depends heavily on the fovea, where cone cells are densely packed. Although the fovea represents only about 0.01% of the visual field, approximately 10% of optic nerve fibers are devoted to this region, underscoring its importance.

- Motion detection: Specialized retinal circuits detect movement by analyzing timing differences in light stimulation across neighboring retinal areas. Research confirms that motion processing begins in the retina, not solely in the brain.

Through these integrated processes, the retina converts simple light energy into the complex visual experience relied upon in everyday life.

Anatomy of the Retina: Layers and Regions

The retina is a highly organized structure located between the vitreous humor and the choroid. Although only about 0.5 mm thick, it contains ten precisely arranged layers that enable the conversion of light into neural signals.

Macula vs Peripheral Retina

The macula lutea is a yellowish region located temporal to the optic disc and represents the most sensitive area of the retina. Measuring about 5.5 mm in diameter, it owes its color to lutein and zeaxanthin, pigments that filter blue light and protect against oxidative damage. At its center lies the fovea, a small depression densely packed with cones that provides the sharpest central vision.

The peripheral retina serves a different function, supporting side vision and night vision. It contains a much higher proportion of rod cells, making it well suited for motion detection and low-light conditions rather than fine detail.

Retina Layers: From Inner Limiting Membrane to RPE

From the inner to the outer surface, the ten retinal layers are:

- Inner limiting membrane: A smooth boundary adjacent to the vitreous, formed by Müller cell processes

- Nerve fiber layer: Axons of ganglion cells forming the optic nerve

- Ganglion cell layer: Cell bodies of ganglion cells

- Inner plexiform layer: Synapses between bipolar and ganglion cells

- Inner nuclear layer: Cell bodies of bipolar, horizontal, and amacrine cells

- Outer plexiform layer: Synapses between photoreceptors and inner nuclear layer cells

- Outer nuclear layer: Cell bodies of rods and cones

- External limiting membrane: Junctional barrier between photoreceptor cell bodies and segments

- Photoreceptor layer: Inner and outer segments of rods and cones

- Retinal pigment epithelium (RPE): Outermost layer supporting photoreceptors

Gross anatomy of the retina

The retina extends from the optic disc posteriorly to the ora serrata anteriorly, where it meets the ciliary body. The distance from the optic disc to the ora serrata measures approximately 23–24 mm temporally and about 18.5 mm nasally.

Central vs. peripheral retina

The central retina is thicker than the peripheral retina due to the dense packing of photoreceptors, particularly cones. The central retina contains predominantly cones, while the peripheral retina is rod-dominant.

In the central retina, cone axons form the Henle fiber layer, a feature absent in the peripheral retina. The inner nuclear layer is also thicker centrally, reflecting a higher concentration of neurons connected to cones. Overall, the nerve fiber, ganglion cell, and inner plexiform layers are substantially thicker in the central retina.

Common Retinal Conditions and Their Symptoms

Retinal diseases affect millions of people worldwide. The most common conditions include diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, and retinal vein occlusion. These disorders can significantly impair both central and peripheral vision.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

AMD primarily affects the macula, leading to gradual loss of sharp central vision. Early symptoms include blurred central vision and distortion of straight lines. As the condition progresses, colors may appear less vivid, and difficulty seeing in low light may develop. Peripheral vision is usually preserved.

Diabetic Retinopathy and Hypertensive Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy results from damage to retinal blood vessels caused by chronic high blood sugar. Early stages may be asymptomatic, with progression marked by fluid leakage and later abnormal vessel growth that can bleed into the vitreous.

Hypertensive retinopathy develops when elevated blood pressure damages retinal vessels. Studies indicate that approximately 66% of individuals with hypertension show signs of this condition. Risk is higher in smokers, individuals of African-Caribbean descent, and those with long-standing hypertension.

Retinal Detachment and Retinal Tears

Retinal detachment occurs when the retina separates from its underlying support tissues, often beginning with a retinal tear caused by vitreous traction. Risk factors include aging, high myopia, prior eye surgery, ocular trauma, and family history.

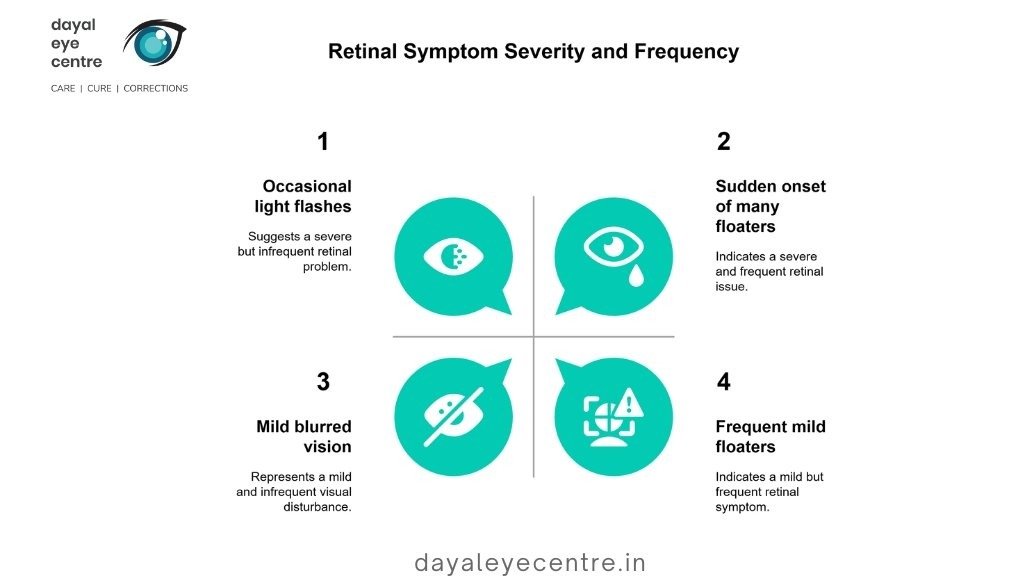

Symptoms: Floaters, Flashes, and Vision Loss

Common warning signs across retinal conditions include:

- Floaters: Sudden appearance of dark spots or squiggly lines, especially in large numbers

- Flashes: Brief flashes of light resembling lightning or stars

- Vision changes: Blurred vision, shadows, peripheral darkening, or a curtain-like effect

Many retinal conditions respond well to early treatment. However, the sudden onset of floaters combined with flashes or a curtain-like shadow requires immediate medical attention, as it may signal retinal detachment—a true ophthalmic emergency.

How to Protect and Care for Your Retina

Your retina needs regular care to stay healthy, yet many people overlook this important part of eye health. Routine check-ups help maintain this complex tissue that allows you to see the world around you.

Eye Exam Frequency Based on Risk Factors

If you are between 18 and 39 years old, a comprehensive eye exam is recommended every 2–4 years. Adults aged 40–64 should have exams every two years, while those aged 65 and older should be examined annually. Some factors require more frequent evaluations, including:

- Family history of eye disease (especially retinoblastoma or macular degeneration)

- Diabetes or high blood pressure

- Previous eye surgery or eye injury

- Severe nearsightedness (high myopia)

- African American or Hispanic heritage

Routine vision screenings at school or work do not thoroughly evaluate the retina. Only a dilated eye examination allows your doctor to properly assess all ten retinal layers.

UV Protection and Eye Safety Measures

Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation can damage the retina and increase the risk of conditions such as macular degeneration. To protect your eyes:

- Wear sunglasses that block 100% of UVA and UVB rays

- Choose wraparound or larger frames for better coverage

- Wear a wide-brimmed hat, especially between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. when sunlight is strongest

Nutrition and lifestyle for retinal health

Diet plays a key role in maintaining retinal health. Foods that support retinal function include:

- Dark leafy greens rich in lutein and zeaxanthin

- Fatty fish high in omega-3 fatty acids

- Brightly colored fruits and vegetables containing antioxidants

If you smoke, quitting significantly lowers the risk of macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. As with other tissues in the body, the retina benefits from overall healthy lifestyle habits. For individuals with diabetes, good blood sugar control is especially important for protecting retinal structure and function.

When to See an Eye Specialist

Talk with your eye doctor immediately if you notice:

- Sudden appearance of floaters or flashes of light

- Dark spots or curtains moving across your vision

- Quick loss of side vision

- Straight lines suddenly appearing wavy

Getting help early often prevents permanent damage to your retina. Most serious retinal conditions worsen if left untreated, potentially leading to vision loss that cannot be reversed.

Conclusion

The retina is a remarkable window into your overall health. Although only about half a millimeter thick, this delicate tissue converts light into the colorful, detailed images you see every day. Because the retina is an extension of the central nervous system, it provides doctors with a unique, noninvasive view of brain health.

Like a camera lens that requires proper care, your eyes—and especially your retina—need protection and attention. The retina’s complex structure, composed of ten distinct layers and millions of specialized cells, supports daily activities such as reading, recognizing faces, and performing detailed tasks through the macula and fovea.

Protecting retinal health means taking a proactive approach. Regular eye examinations are essential, particularly if you have risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of eye disease. Wearing UV-protective sunglasses, eating a nutrient-rich diet, and watching for early warning signs all help preserve vision over time.

Pay close attention to symptoms such as floaters, flashes, or sudden vision changes. These may indicate serious conditions like macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, or retinal detachment. Because the retina cannot heal itself once damaged, timely treatment often determines whether vision can be preserved.

Although treatments for retinal diseases have advanced significantly, prevention remains the most effective strategy. Managing blood sugar and blood pressure, maintaining good nutrition, and attending regular eye check-ups directly support retinal health. With proper care and monitoring, you can protect this vital part of your vision for years to come.

FAQs

What is the main function of the retina in the human eye?

The retina’s primary function is to convert light into neural signals. It captures incoming light and transforms it into electrical and chemical signals that travel through the optic nerve to the brain, allowing visual perception.

How many layers does the retina have, and what are they?

The retina has ten distinct layers, ranging from the inner limiting membrane to the outermost retinal pigment epithelium. Each layer plays a specific role in light detection, signal processing, and transmission to the brain.

What are common symptoms of retinal problems?

Common symptoms include sudden appearance of floaters, flashes of light, blurred or distorted vision, darkening of peripheral vision, and curtain-like shadows across the visual field.

How often should I have my eyes examined for retinal health?

In general, adults aged 18–39 should be examined every 2–4 years, those aged 40–64 every two years, and individuals 65 and older annually. People with risk factors such as diabetes or a family history of eye disease may require more frequent exams.

What lifestyle changes help protect retinal health?

Protective measures include wearing UV-blocking sunglasses, eating a diet rich in leafy greens and omega-3 fatty acids, quitting smoking, managing diabetes and hypertension, maintaining a healthy weight, and seeking prompt care for any sudden vision changes.