Your eye doctor diagnoses different types of retinal detachment based on specific characteristics. Tractional retinal detachment (TRD) differs from other types in several important ways. Understanding these differences helps determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

No Retinal Breaks in TRD vs Rhegmatogenous RD

Unlike rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD), which occurs due to holes or tears in the retina, tractional retinal detachment develops without retinal breaks. RRD can be compared to a puncture in a water balloon, whereas TRD follows a different mechanism. In TRD, proliferative membranes in the vitreous or on the retinal surface exert traction on the neurosensory retina, pulling it away from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) when the traction becomes strong enough.

Although retinal breaks are typically absent in pure TRD, they may develop later if strong traction from extensive fibrovascular tissue creates full-thickness retinal tears. This results in a combined tractional–rhegmatogenous detachment, which requires a more aggressive surgical approach. As with any medical condition, treatment must address all components of the pathology.

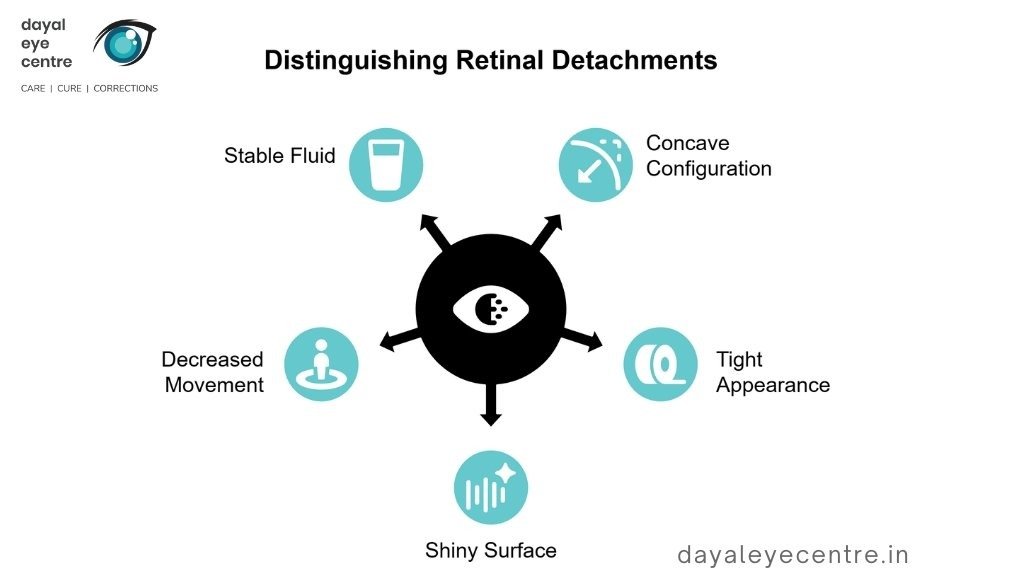

Concave Retinal Elevation Pattern in TRD

The configuration of the detached retina provides important diagnostic clues. In tractional retinal detachment, the elevated retina typically assumes a concave shape toward the pupil. The detached retina often appears taut, with a shiny surface and reduced mobility.

This contrasts with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, which usually shows a convex configuration, resembling a hill rather than a valley. Another distinguishing feature is that TRD is generally shallower than rhegmatogenous detachment, and the subretinal fluid does not shift with changes in head position. This lack of fluid movement helps clinicians differentiate TRD from other types of retinal detachment.

Role of Fibrovascular Membranes in TRD

Fibrovascular membranes (FVMs) play a central role in the development of tractional retinal detachment. These membranes form when scar tissue or abnormal tissue grows on the retinal surface, most commonly in conditions such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The process usually begins with new blood vessels growing from existing retinal vessels into the vitreomacular interface, accompanied by fibrous tissue and contractile elements.

These membranes behave like shrinking plastic wrap— as they contract, they pull on the retina, causing deformation and eventual detachment. The relationship between the vitreous gel and the macula is particularly important in this process, which explains why posterior vitreous detachment can be protective against TRD in some cases.

In severe disease, residual vitreous gel on the inner retinal surface can act as a scaffold for further fibrous proliferation, worsening traction. In some instances, these membranes lead to tractional retinoschisis, a condition that can be mistaken for tractional retinal detachment because of their similar appearance on examination.

Primary Systemic and Ocular Causes of TRD

Several systemic and ocular conditions can lead to tractional retinal detachment by pulling the retina away from its normal position. Understanding these causes helps guide clinical decision-making and patient counseling.

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy with Tractional Retinal Detachment

Diabetes mellitus is the most common cause of tractional retinal detachment worldwide. In proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), chronic hyperglycemia damages the retinal microvasculature, leading to capillary closure and retinal hypoxia. The body responds by activating protein kinase C and increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels. These factors stimulate the growth of new blood vessels that breach the internal limiting membrane and extend into the vitreous cavity. Over time, these vessels form fibrovascular tissue with contractile properties that exert traction on the retina.

Negative pressure generated by the retinal pigment epithelium pump in the subretinal space contributes to the characteristic concave configuration of the detached retina. Studies show that TRD is the most common indication for vitrectomy in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Postoperative visual outcomes are often favorable; one study reported improvement from 20/800 to 20/160 over a 10-month follow-up period.

Retinal Vein Occlusion and Sickle Cell Retinopathy

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) can lead to tractional retinal detachment, particularly when the macula is involved. Ischemic retinal areas stimulate neovascularization similar to that seen in diabetic retinopathy, resulting in fibrovascular membrane formation. Visual outcomes after surgical treatment vary widely, typically ranging from 20/40 to 20/400.

In sickle cell retinopathy, abnormal red blood cells obstruct small retinal vessels, leading to ischemia and the development of characteristic sea-fan–shaped neovascularization. These vessels can later become fibrotic and exert traction. Despite these changes, significant vision loss is relatively uncommon, occurring in approximately 12% of untreated cases. When vision loss does occur, it is most often due to vitreous hemorrhage or tractional retinal detachment.

Uveitis, Trauma, and Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy

Patients with uveitis have a higher risk of retinal detachment compared with the general population. Infectious uveitis, particularly due to cytomegalovirus or varicella zoster virus, is more strongly associated with detachment. Tractional retinal detachment occurs in approximately 1.5% of eyes affected by uveitis.

Ocular trauma can lead to TRD through inflammation and disruption of the blood–retinal barrier, which attracts cells that promote scar formation. Severe blunt trauma may result in extensive scarring along the posterior vitreous surface, leading to macular tractional detachment.

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) represents the end-stage scarring response following retinal injury and occurs in approximately 5–10% of retinal detachment cases. PVR involves the formation of cellular membranes within the vitreous cavity and on retinal surfaces. Contraction of these membranes can cause tractional detachment, reopen existing retinal breaks, or create new ones.

Pediatric-Specific Etiologies of TRD

Children experience unique causes of tractional retinal detachment that require specialized approaches to care. Understanding these conditions helps parents and clinicians identify problems early.

Retinopathy of Prematurity and Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) affects approximately 68% of infants weighing less than 1,251 g. Two factors are especially important: gestational age and birth weight. For each additional week in utero, an infant’s risk of developing threshold ROP decreases by about 19%. During normal eye development, relatively low oxygen levels stimulate healthy blood vessel growth. In premature infants, early exposure to room air creates excess oxygen levels, which initially damage developing vessels and later trigger abnormal vessel growth that can exert traction on the retina. Despite treatment, about 22% of aggressive ROP cases progress to tractional retinal detachment. These detachments typically show abnormal, tortuous posterior vessels with a flat network of neovascular tissue.

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) resembles ROP on examination but occurs without a history of prematurity. It is an inherited condition associated with mutations in genes such as FZD4, NDP, and LRP5. Vitreoretinal adhesions are especially strong in avascular peripheral retina, making surgical management challenging. Surgical reattachment is successful in approximately 85.7% of cases, with visual improvement reported in 71.4%.

Persistent Fetal Vasculature and Incontinentia Pigmenti

Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV) causes tractional retinal detachment through contractile fibrovascular stalks that pull on the retina. PFV accounts for about 5% of childhood blindness in the United States. Most cases are unilateral and idiopathic, although bilateral involvement may be associated with systemic syndromes. Contrary to earlier beliefs, PFV can be progressive rather than stable, with retinal tears developing as the eye grows.

Incontinentia pigmenti affects the eyes in approximately 35% of patients. In these children, tractional retinal detachment is the most serious and common ocular complication. Extensive fibrous tissue forms anterior to and within the vitreous, pulling the retina forward. Early detection followed by preventive laser therapy can help prevent severe vision loss.

Toxoplasma and Toxocara Retinitis

Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, accounts for about 7.2% of cases of ocular inflammation. When the retina is involved, tractional retinal detachment may occur, typically following severe intraocular inflammation in approximately 90% of acquired cases. Visual outcomes are often poor, with legal blindness reported in about 56% of cases complicated by detachment.

Toxocara canis, a parasite transmitted through dog feces, produces a characteristic pattern of tractional macular detachment. These detachments show spoke-like retinal folds extending from peripheral inflammatory nodules toward the optic nerve. Although surgical reattachment is successful in about 83% of cases, final visual outcomes depend largely on preoperative vision and whether the central macula is involved by folds.

Risk Factors and Preventive Considerations

Prevention of tractional retinal detachment relies on managing underlying risk factors and ensuring timely screening. Recognizing these factors allows intervention before vision-threatening complications occur.

Uncontrolled Diabetes and Delayed Screening

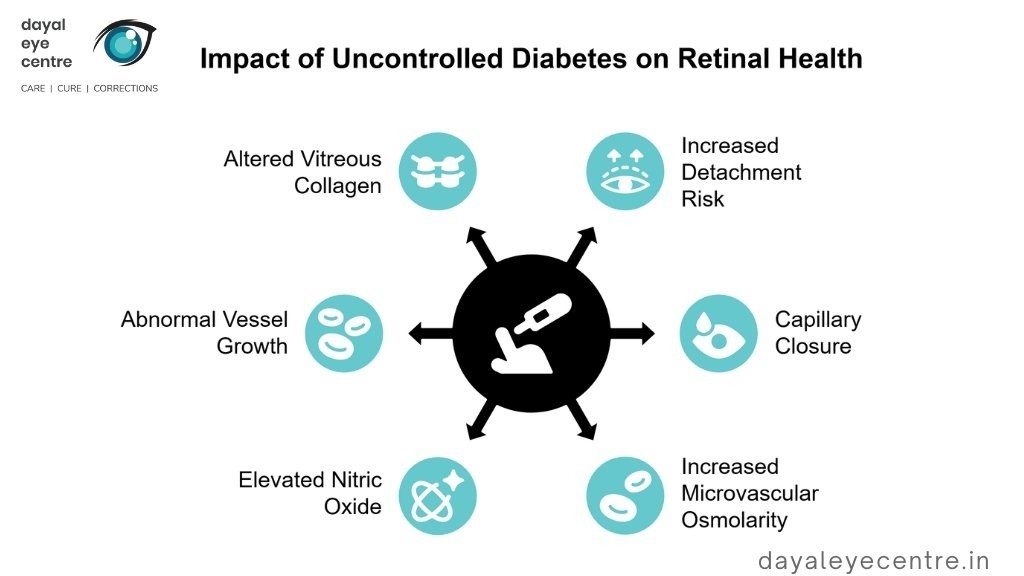

Uncontrolled diabetes significantly increases the risk of tractional retinal detachment, with approximately 5.8% of diabetic patients developing this condition. Poor glycemic control is consistently associated with higher detachment rates compared with well-controlled diabetes. Systemic health plays a critical role in ocular outcomes. Evidence also suggests a relationship between lipid control and detachment risk, with slightly higher rates observed in patients with poorly controlled LDL cholesterol.

Chronic hyperglycemia triggers several harmful retinal processes, including capillary closure, increased microvascular osmolarity, and elevated nitric oxide levels. These changes promote abnormal neovascularization and alter vitreous collagen cross-linking, generating tractional forces that can detach the retina. Regular comprehensive eye examinations remain essential to detect retinal changes early and prevent progression to detachment.

Importance of Early Detection in ROP

In retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), gestational age and birth weight are the primary risk factors. For every additional week of gestational age, the likelihood of developing threshold ROP decreases by 19%, while each 100 g increase in birth weight reduces the risk by 27%. Oxygen therapy is another critical factor—each 12-hour period with transcutaneous PO₂ ≥ 80 mmHg doubles the risk of ROP.

Encouragingly, current screening guidelines provide clear direction, recommending eye examinations for infants born at ≤30 weeks of gestational age or weighing ≤1,500 g, beginning four weeks after birth. These coordinated early detection programs have proven highly effective, reducing the incidence of severe ROP from 13.6% in 2002 to just 0.76% in 2021 in a Colombian study. Such programs focus on three key components: maintaining oxygen saturation below 94%, performing weekly eye examinations, and implementing kangaroo mother care.

Protective Measures Against Ocular Trauma

Ocular trauma is a common cause of tractional retinal detachment due to inflammation and disruption of the blood–retinal barrier. To help protect your eyes and reduce the risk of trauma-related detachment:

- Wear appropriate protective eyewear during hazardous activities

- Use proper eye protection during sports and in work environments

- Seek immediate medical attention after any eye injury

This simple measure can substantially reduce trauma-induced retinal detachments.

Following any eye injury, prompt evaluation by your eye doctor is crucial. Early diagnosis of retinal tears allows for outpatient retinopexy—a straightforward procedure that is highly successful in preventing progression to retinal detachment. The interval between tear formation and detachment often provides sufficient opportunity for intervention, but only if medical care is sought immediately.

Conclusion

Tractional retinal detachment requires immediate medical attention to prevent permanent vision loss. Throughout this article, we have explored the causes of this serious eye condition, which occurs when scar tissue pulls the retina away from its normal position. Diabetic retinopathy remains the leading cause, affecting a growing number of patients who may ultimately require vitrectomy surgery.

Unlike other forms of retinal detachment, tractional retinal detachment develops through a distinct mechanism. It typically begins without retinal breaks and shows a characteristic concave configuration toward the pupil. Fibrovascular membranes generate tractional forces that gradually separate the light-sensing retina from the underlying supportive tissue.

The risk of tractional retinal detachment extends beyond diabetes. Other contributing conditions include retinal vein occlusion, sickle cell retinopathy, uveitis, ocular trauma, and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. In children, unique challenges arise from conditions such as retinopathy of prematurity, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, persistent fetal vasculature, and certain infections.

Managing risk factors is essential, as many cases can be prevented with appropriate care. Uncontrolled diabetes significantly increases risk, while delayed screening allows the condition to progress to advanced stages before detection. Regular comprehensive eye examinations are critical for identifying retinal changes early.

As with many medical conditions, prevention is more effective than treatment. Controlling underlying systemic diseases—particularly diabetes—combined with routine eye screening can substantially reduce risk. In premature infants, established screening protocols have dramatically reduced the incidence of severe retinopathy of prematurity.

Although tractional retinal detachment presents serious challenges, early detection and timely treatment offer the best chance of preserving vision. Understanding the causes and risk factors empowers patients and caregivers to recognize warning signs early and seek prompt medical care. Awareness and timely intervention remain the strongest defenses against permanent vision loss.

FAQs

What is the primary cause of tractional retinal detachment?

The most common cause of tractional retinal detachment is proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In this condition, abnormal blood vessel growth and scar tissue formation on the retina contract and pull the retina away from its normal position.

How does tractional retinal detachment differ from other types?

Tractional retinal detachment occurs without initial retinal breaks and has a characteristic concave configuration toward the pupil. It is caused by fibrovascular membranes exerting traction on the retina, unlike rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, which involves retinal tears.

What are some risk factors for developing tractional retinal detachment?

Major risk factors include uncontrolled diabetes, delayed eye screening, premature birth (related to retinopathy of prematurity), and certain inherited conditions. Regular comprehensive eye examinations are essential for early detection.

Can tractional retinal detachment occur in children?

Yes, tractional retinal detachment can affect children. Pediatric causes include retinopathy of prematurity, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy, persistent fetal vasculature, and infections such as toxoplasmosis.

How can tractional retinal detachment be prevented?

Prevention focuses on controlling underlying conditions, especially diabetes, maintaining regular eye screenings, using protective eyewear to prevent ocular trauma, and adhering to screening protocols for premature infants. Early detection and timely intervention are key to preserving vision.